Rangeley Renaissance

July 11, 2018

SCA Articles

SCA Articles

By 1900 the Rangeley boat, a design influenced by the Adirondack guideboat and the St. Lawrence River skiff, was firmly established as the guidebat on Maine’s lakes. Only recently, however, has the Rangeley been rediscovered, this time by Robert Lincoln of RKL Boatworks, who builds this traditional design in his own contemporary fashion.

It’s already 9:30 this foggy, December morning before Robert K. Lincoln, the tall, bearded 38-year-old proprietor ofRKL Boatworks on Maine’s Mount Desert Island, has time to pour himself some coffee, settle down in the living room of the home he built from native spruce, and talk about the Rangeley boats. The 17-foot “full-size” Rangeley and the 14-foot Little Rangeley have vaulted RKL, in the span of a mere ix years, not only into the sporting limelight but into the forefront of the comparatively few builders specializing in small wooden craft.

The contribution of Bob Lincoln and RKL Boatworks, however, is only the most recent chapter in the history of the Rangeley boat, a hi tory that began even before boats of the same name appeared on the Rangeley, Maine lakes: Rangeley itself, Mooselookmeguntic, Cupsuptic, Richardson, and Umbagog. The era following the Civil War was marked by newfound prosperity for many in the Northeast, and with affluence came leisure. Recreation became an industry; hotels, lodges, camps, and inns sprang up in the Adirondacks, the Thousand Islands of the St. Lawrence River in upstate New York, the lake districts of Maine. The common denominator of these areas was outstanding fishing, and although early versions of the famed Adirondack guideboat had been in use since the 1840s, the pioneering sportsman could expect to angle in anything from the birch-bark canoe to a crudely hewn rowboat.

But as guiding was refined to a profession of economic importance not only to the guides themselves but to the establishments employing them, it soon became apparent that a boat was needed to satisfy a variety of criteria. Such a boat had to be responsive and maneuverable under oars, able to hold a line in the water; it had to be rugged and seaworthy, able to ride out a blow; it had to be stable and comfortable to fish from. The Adirondack guideboat attempted to fill these needs, and it is no accident that the other classic guideboats that evolved in the Northeast display similarities to it.

But if the light, easily portaged Adirondack guideboat remained a regional favorite, conditions elsewhere dictated adaptations improvement. In 1868, Xavier Colon built the first St. Lawrence River skiff in C layton, New York. A kind of marriage of the guideboat and the canoe, the St. Lawrence River skiff was of lapstrake (“clinker-built”) construction, double-ended, and up to 23 feet in length. It had the singular characteristic of often being used as a rudderless sailboat (it was steered by trimming the sail and redistributing the ballast) as well as a rowboat, and it was ideally suited for negotiating the long distances between fishing hotspots. The guides embraced the boat enthusiastically, and by the 1880s the graceful, upswept lines of the St. Lawrence River skiff were as much a part of the Thousand Islands as bass and pike.

According to the research of Paul McGuire, professor of history at Gould Academy and an authority on the development of Maine’s inland watercraft, it was a St. Lawrence River skiff design from Ogdensburg, New York, that inspired the original Rangeley boats in the 1870s. McGuire contends that the first Rangeleys were built by Luther Tebbets at the confluence of the Rangeley and the Kennebago for the members of the Oquossoc Angling Club.

A slightly different account is given by John Gardner, associate curator of small craft at Mystic Seaport in Connecticut and the man primarily responsible for preserving the drafting lines and history of many classic small boats. Gardner believes the immediate predecessor of the Rangeley was an unnamed design from New York state featuring a small , “high-tucked” transom stem instead of the double end. These boats also had an extreme curve of the deck from bow to stem. Gardner admits, however, that by the latter portion of the 19th century, the standard Rangeley boar was a double-ender.

The third explanation has been advanced by Edwin Barrett. He maintains that his father, Thomas, built the model for the original Rangeley boat in 1880. The elder Barrett, who had lost his hearing at age 15 from meningitis, left Maine to attend Baxter School for the Deaf in Portland in 1881, and “by mutual agreement” his brother Charles started the Barrett shop in Rangeley.

Edwin Barrett described how early Rangeleys were built. “The first boats were rowboats, pointed on both ends, 17 feet long, 44 inches wide, and 16 inches deep, with three seats and weighing 140 pounds. An average of 40 boat were built a year.

“These boats were built different than most ,” Barrett explains. “The bottom, which was 4-inch wide pine, was rabbeted for the planking, the oak stems fastened to each end, then hung bottom side up on horses. The 5/16-inch native cedar planking was fastened together through the 7 inch lap with swede iron tacks. The laps were coated with a heavy coat of white lead and yellow ochre below the waterline. The tacks were 3 1/2 inches apart.

“The boat was then turned over, decks installed and gunwales attached. Then the boat was ribbed with 5/8-inch half-round oak ribs placed between each row of tack and fastened with swede iron clout nails. The sears and floor were installed next. The floor was designed to be taken out when the boat was cleaned or painted. Block and sockets were attached to the gunwales to accept the oarlocks.

“The boats were then painted with a primer of mostly linseed oil,” Barrett says, “then one coat of white lead and oil inside, being sure to fill all seams, then a coat of green paste and oil outside. They were stored until shipment, and then the boats were given a fresh coat of paint.”

It’s probably safest to say that there are elements of truth in all the accounts of the Rangeley’s origins; the names of boats, people, and places are impossible to unravel from the larger fabric of the Rangeley’s history. Regardless, by the turn of the century it was firmly established as the guideboat not only on the Rangeley chain, but on Sebago and the Belgrade Lakes as well. It fulfilled the criteria for a working guideboat, winning particular admiration for its ability to take rough weather.

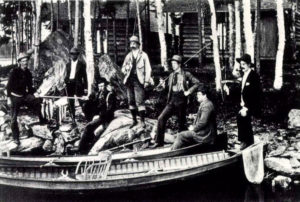

The lakes of Maine are among the few testing grounds of American fly-fishing where the tackle, traditions, and concerns of the sport were shaped, where fly-fishing as we practice it today emerged as a force on the American sporting scene. The brook trout (“squaretail” in Maine) was the principal quarry in the stream-connected Rangeleys, and it was in this region that the gaudy wet-fly patterns with the lilting names were tied and popularized: It was a time of catgut, silk lines and stout twohanded rods. In period photographs the mannered poses of the “sports” convey an aura of formality: starched collars, neckties, waistcoats with dangling watch chains, jodhpurs, wide-brimmed fedoras, waxed moustaches. And the guides in their suspenders hoist the day’s catch of squaretails, with perhaps a togue (lake trout) or landlocked salmon hanging from the stringer as well.

Often as not, these portraits Df the sporting life in turn-of-the century Maine include one or more Rangeley boats, “essential,” as John Gardner has rightly pointed out, “but taken for granted.” Boats of various lengths and with slight differences in details are shown, but the Rangeley “look” is unmistakable. There is the high, plumb bow that suggests the Adirondack guideboat; the gracefully curving sheer borrowed from the St. Lawrence River skiff and Gardner’s unnamed New York design; the buxom flare of the lapstrake hull; the overall impresion of shapeliness, substance, and strength. The Rangeley boats lend a sense of motion and vitality to these otherwise stiff portraits. It is only now that the Rangeley’s role as a supporting actres on the stage of early American fly-fishing is beginning to be appreciated.

The guides knew their boats intimately: many were boatbuilders themselves during the off-season . The many hours of handwork that went into construction of a Rangeley from hewing the pine keel to steam-bending the oak ribs to fairing the planking necessitated a painstaking attention to detail. While the boat represented a guide’s livelihood and was meant for hard use, it is impossible not to believe that they took a kind of Yankee pride in turning out a craft that was beautiful a well as functional.

The Barretts were established as the first name in Rangeley boats, but others had followings as well: Luther Tebbets, Hod Loomis, Fred Conant, Arthur Amberg, Rufus Crosby, Harold Ferguson, Martin Fuller. The 17 -foot model became the norm, but the definition of “Rangeley boat” has never been a narrow one. Shorter boats were built specifically for smaller waters, and a noteworthy deviation from the classic lapstrake hull has survived in a few examples of the “eggshell” Rangeley. In this design, the top two planks are lapsttake, the rest smooth-sided carvel planking.

The living link between the Rangeley boat’s past and present is Herbert N. Ellis, who, assisted by his son Hal, still builds them in the traditional style from cedar strakes and oak ribs at his shop in the town of Rangeley. Elli apprenticed to Frank Barrett in 1936, earning 25¢ per hour, and when Barrett’ health declined, Ellis bought him out in 1938 for $2,500.

It was an era of change for the Rangeley boat. Outboard motors had come into vogue, and the double-enders so elegantly suited to rowing were at a disadvantage as working guideboats. Many of the lovely double-enders were converted to transom stems. In an interview with Paul McGuire published in Wooden Boat magazine, Herb Ellis recalls being summoned to Moose one fall to cut the ends from 20 Rangeleys and to fit them with square stems to accommodate outboard motors. Indeed, from the time of Ellis’s takeover of the Barrett shop, virtually all the Rangeleys produced were square-stem models. Ellis developed three styles, designated simply as the number one, the number two., and the number three. The number one was also called the “fantail” transom, and because the taper Df the hull below the waterline was essentially that Df a double-ender, it retained its excellent rowing qualities. Ellis recommended nothing larger than a five-horsepower motor for the number one, and for motors up to seven-horsepower he designed a Rangeley with a wider stem and round-bottomed transom, the number two. The number three, for outboards up to to-horsepower, was deeper, with stouter ribs and a wider transom.

After World War II , the majority of Ellis’s business was in number three Rangeleys, although he did build a few of the other models, even an DccasiDnal dDuble-ender. But the market for wooden boats was weakening. A Rangeley could well be called a work of art; at the very least, it was a sterling example of the boat builder’s craft, of a highly refined skill possessed by only a handful. Fishing the lakes DfMaine from a Rangeley bDat was grand sport, but the boats were expensive to purchase and maintain compared to cheaper aluminum models. These crafts may have been “decadent and inferior in design,” as John Gardner described them, but they were rugged, maintenance free, and could be equipped with even larger outboards. By the mid-1950s, the demand for Rangeley boats was too small to support Herb Ellis, and he turned to the more profitable occupations of home construction and cabinetmaking. Although there was sporadic work in repairing old Rangeleys, for almost 20 years this classic guideboat languished .

The single shaft of light during the Rangeley’s dark ages came in 1968, when John Gardner, in his capacity as technical editor of National Fisherman, published the lines of an Ellis Rangeley number one in the ownership of the Red Spot Fishing Club on Lake Umbagog. In the accompanying article, this relentless pursuer of “lost” small boat designs claimed: ‘This is the first time the lines for a Rangeley boat have been printed, to the best of my knowledge, and I’ve been on the lookout for such for years. Such oversight, neglect, indifference, or whatever it is, on the part of small craft designers and historians is hard to comprehend, for this distinctive American sporting boat has been in use on the Rangeley lakes of Maine for something like 100 years now, and was well known to past generations of fishermen for its numerous excellent characteristics.” The serve ice performed by Gardner in preserving the lines of the Rangeley and other traditional craft cannot be overestimated (his Building Classic Small Craft, published in 1977, is a bible for those who are passionate about such vessels). But it would be 10 years before his effort to renew interest in this “distinctive sporting boat” would bear fruit. Enter Robert K. Lincoln. He and his wife settled on Mount Desert Island in 1971, where they had both been “summer people.” Lincoln was employed as an interior yacht carpenter for the Hinckley Company and then worked for a housing contractor. He was an independent carpenter in 1976 when he set out to build a cedar-strip canoe to replace a fiberglass model he’d destroyed running whitewater. With no previous experience in boat building per se and relying only on his carpentry skills, an obsessive attention to detail, and a copy of David Hazen’s The Stripper’s Guide to Canoe Building, Lincoln achieved such impressive results in terms of workmanship and in sheer visual attraction-thin bands of native cedar glowing beneath a transparent skin of fiberglass—that several individuals, upon seeing the canoe atop Lincoln’s auto, immediately inquired about having one built.

“In most things I’ve done, I’m not school taught,” says the angular, blue-eyed Lincoln. He has the lean, athletic body of an oarsman; in the past, he’s rowed a single scull and stroked a four with coxswain. “I’ve started with some knowledge, then I’ve developed my own techniques.

Lincoln further describes himself as a “tinkerer and innovator.” After only two canoes, Lincoln embraced the WEST System, a variant of epoxy cold molding invented by Gougeon Brothers of Bay Ciry, Michigan. The WEST (Wood Epoxy Saturation Technique) System uses epoxy resin not only to bond fiberglass cloth to the hull, but to impregnate the wood itself, thus eliminating the possibility of delamination and sealing out water and air. The resulting “monocock” hull is amazingly strong in relation to its weight, so there is no need for interior ribs, and because the epoxy cures clear, it allows the boats to be finished in bright colors. Lincoln has continually experimented with epoxy resins; he now uses the Gougeon product for fastening planking and the System Three brand for sheathing the hulls because of resiliency and its superior resistance to ultraviolet damage. Additional protection again t ultraviolet rays is provided by two coats of Awlgrip alyphatic urethane, which also enhances the already dazzling beauty of the woodwork.

“We started with the canoes, but living in a large boating area, it wasn’t long before people came to me wanting different kinds of dinghies,” recalls Lincoln. “Not being a schooled designer myself, I didn’t have the personal capability to design my own dinghy. That combined with the fact that Maine is a very tradition oriented area in boating, it was quite natural for me to become involved with traditional designs.

By 1977, Lincoln was building boats full time, and his WEST System cedar-strip canoes and dinghies continued to feature the flawless finish and craftsmanship that have become RKL’s trademark. Ironically, it was Lincoln’s lack of design expertise that led to his first Rangeley. It would make good copy to report that the order came from an aged fly fisherman longing to recapture a scrap of his tattered youth. In fact, however, a man approached Lincoln in 1978 wanting an unusually stable rowboat in which he could install a sliding seat such as a sculler would employ. Lincoln cast about for ideas, finally settling on the Ellis Rangeley that John Gardner had publicized a decade earlier. Instead of following the original construction of lapped and nailed planks over ribs, however, Lincoln adapted his contemporary techniques to the Ellis design. Nevertheless, the RKL Rangeley-smooth-hulled, free of exterior nails, lacking ribs—displayed the classic lines and performance for which its ancestors had been famed. After researching the history of the boat and perfecting his own version of the Rangeley, Lincoln became convinced that he had found the ideal vehicle for the tradition-conscious fly fisherman.

“Fly fisherman are very aesthetically oriented towards handmade wooden equipment, ” he observes, “split cane rods, for example. But at the same time, they’re appreciative of new technology, such as graphite and boron rods. My version of the Rangeley was ‘something old, something new. ‘ A lot of experimentation and contemporary styling have gone into my boats; certain ly their appearance, finish, and low maintenance reflect modem concerns, but the design remains tradtional.

If it’s possible to assign a date to the beginning of the “Rangeley Renaissance,” it would be 1981. Of course, it did not occur in a vacuum. The revival of interest not just in wooden boats but in traditional American crafts and art forms in general had created a receptive market; indeed, Herb Ellis had been able to return to building his version of the Rangeley on a basically full-time basis. But outside a few wooden boat enthusiasts and a handful of sportsmen, the Rangeley boat was unknown until RKL began its advertising association with Fly Fisherman in 1981 , thus exposing the Rangeley boat to a national sporting audience for the first time. The RKL Rangeley-a traditional form in a contemporary package-was enthusiastically received. During this time, Lincoln added the Little Rangeley to his line, using the knowledge he’d already acquired to take the plans for a IS -foot double-ended Barrett Rangeley and re-design them for a 14-foot square-stem that could handle a small outboard and, at 90 pounds, could be easily carried on top of a car. Also in 1981 Lincoln received a letter from Leon Gorman, president of L. L. Bean, requesting his catalogue.

That request led to an invitation, in early 1982, for Lincoln to show his boats to Mr. Gorman and the Bean staff. There has been at least one RKL Rangeley or Little Rangeley on display in the Bean showroom in Freeport, Maine, ever since. More than a few, captivated by its sleek lines, meticulous worksmanship, and almost luminous finish fish out their checkbooks ,the $3,800 price tag for a Little Rangeley notwithstanding.

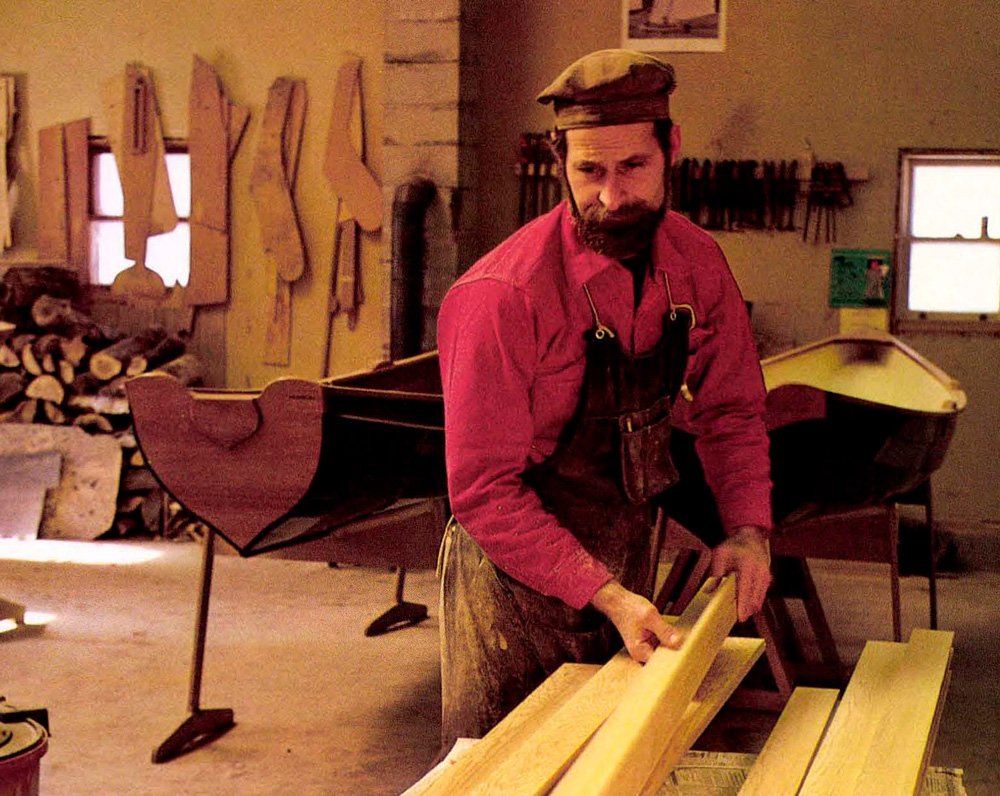

Every other boat RKL turns out is made to order in the shop Bob Lincoln built next to his home. The shop’s cathedral ceiling is supported by mass ive, laminated arches that look as if they belong in a sanctuary. Lincoln built them, too. “They’re fancier than they need to be,” he admits, “but I concluded that the appearance of the shop is important to customers. ” Molds for the various RKL models hang from the ceiling (although he is best known for his Rangeleys, Lincoln still offers canoes and dinghies); adjoining the workroom are a finishing room and a storage room, the three areas providing sufficient space to work on two boats at a time. Lincoln’s single employee-he anticipates hiring more-is Owen Cole, a good-humored Pennsylvania native who shares his boss’s commitment to quality.

Although they are usually made to order, the structural aspects of the RKL Rangeleys are more or less standardized. The customer can still choose the type of wood for the trim, oiled-cedar floorboards, a wide stem (on the full-size Rangeley) for a larger motor, and any number of other options. The hulls are planked on a laminated stem screwed to a one-piece mahogany keel. Strips of western red cedar, one inch wide and 5/16 inch thick, are milled so their edges form mating V’s. As the strips are laid over the mold, these edges are epoxied; the planks are temporarily attached to the mold while the epoxy cures. The hull i then lightly sanded, and the “skin” of epoxy resin and four-ounce fiberglass cloth is applied, one coat on the inside and two coats outside. Finally, two coats of Awlgrip urethane are sprayed on , and the boat is ready for gunwales, thwarts, foredeck, brass fittings, and whatever options the purchaser has specified in his contract. Little wonder, considering the amount of labor invested by Bob and Owen in a full-size Rangeley, that it can take as long as six months to take delivery and the price is in the neighborhood of$4,500.

In 1984, Lincoln began offering the Rangeleys in a more traditional-looking lapstrake hull planked with Bruymzeel mahogany plywood, in addition to his strip-planked models. The construction is not “true” lapstrake: instead of being simply lapped and clench-nailed, as in a genuine clinker-built boat, Lincoln mills the edges of the Bruymzeel planks so they fit in a sort of tongueand-groove arrangement (he calls it “channel-lock” construction) , which allows them to be epoxied rather than nailed The boats are coated with epoxy resin, and the outer hull is painted to the sheer strake, bringing out the lapped lines of the planking. The resulting craft, while slightly heavier than the corresponding strip-planked model, is less expensive: about $4,000 for the Rangeley, $3,400 for the Little Rangeley.

There are some purists, steeped in the history of the Rangeley boat and the traditions of wooden boat building, who still cast a suspicious eye at the creations of Robert K. Lincoln. But even in its heyday, there was latitude in the definition of “Rangeley boat.” There were 13-foot double-enders and 18-foot square stems. There was also the eggshell Rangeley with the smooth planking below the waterline, a precedent for the smooth-hulled RKL designs. The craftsmen of the 19th and early 20th centuries used the techniques and materials available to them, just as Bob Lincoln has done today. Herb Ellis, a product of the 1930s still builds Rangeleys from cedar strakes and oak ribs in the manner he learned from Frank Barrett, and, in the words of historian Paul McGuire: he “doesn’t see any need to change. He doesn’t see himself as being on the cutting edge of wooden boat technology, and he’s no longer a young man. Who knows? IfH.N. Ellis was just starting up and ready to take on the world, he might be at the front of the ranks. ”

McGuire is a fan of the Ellis Rangeley; Herb Ellis and his son, Hal, recently built a number one Ellis Rangeley for McGuire and his wife. Still, he is philosophical about the question of “tradition.” “Bob Lincoln’s work is excellent, and his version of a traditional boat whose original uses and construction methods were vastly different is a fine marriage of old design and modem technology. Whether it is as good or better than the clench-nailed Rangeley is a matter for the zealots to worry about. To my way of thinking, the existence of both types of Rangeley boats makes us all the luckier.”