King Of The Hill

February 27, 2020

SCA Articles

SCA Articles

From high atop a Texas knoll, Greystone Castle’s hunters sally forth to pursue trophy whitetails, game birds and exotic animals from as far away as Asia and Africa.

At my somewhat tender age, I’m not a big fan of change, though I certainly realize that, like death and taxes, it’s a constant in our lives. Of course, it’s easier to accept change when it makes us happier or healthier, but in my mind there’s always the thought, “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”

Such were my emotions when talking with Jennifer Miller, the sales and marketing director at Greystone Castle, a 6,500-acre sporting venue about 50 miles west of Ft. Worth, Texas.

Seven years earlier I had enjoyed a wonderful hunt there for white-tailed deer, blackbuck and upland birds.

“We’ve made a number of changes since you were last here,” Jennifer said, “all of them good. But we’d like you to experience them for yourself.”

But how can something so good be made even better? I remember thinking.

“Although we’re primarily known for our bird hunting,” said Jennifer, “in the last few years we’ve enhanced our whitetail operation by bringing in superior genetics and expanding our management program to include careful culling of inferior deer and high-protein feeding.”

Beginning in October, she added, they would offer trophy whitetail hunts to nine Gold Medal clients . . . and, would I like to be one them? Do coyotes howl at the moon? Does a hundred-pound sack of flour make a really big biscuit?

After carefully considering my answer for three or four milliseconds, I accepted her generous offer. However, after thinking about it, I decided I’d rather that my son, Scott, have the opportunity to take one of Greystone’s giant whitetails.

Scott is an avid deer hunter in our home state of South Carolina, where the odds of killing a record-book buck are about as good as winning the lottery. Not surprisingly, after similar careful consideration he announced that he was definitely on board with my plan. So, while Scott pursued a big whitetail, I’d once again hunt blackbuck, a strikingly beautiful little antelope threatened with extinction in its native India, but now flourishing on the rolling woodlands and fields at Greystone.

So, in early October Scott and I merged onto 1-20 in Columbia, then drove due west for the next day and a half before arriving at Greystone’s gate and the winding road leading up to the castle.

Greystone Castle is a truly impressive sight, decidedly unique not only in the Lone Star State but in the entire nation. Built in the 1980s by a gentleman who was fascinated with 16th century English castles, the concrete and stucco edifice sits atop a tall bluff overlooking the ghost town of Thurber, where in the 1880s its 10,000 inhabitants worked one of the largest coal mines in Texas while also producing paving bricks used throughout the South.

By the 1920s, after the conversion of locomotives from coal to oil gradually reduced demand and lowered prices, virtually all of the miners had moved on to other jobs in other locations. Nature has since reclaimed the land, breaking down the brick walls and chimneys of the old town and hiding them beneath a dense canopy of trees. The only landmarks that remain are the Thurber Cemetery with over a thousand graves, the Thurber factory smokestack, and a handful of restored buildings.

In the mid-1990s Greystone’s original owner decided to sell the site after completing two of the castle’s 30-foot-tall walls. The new owners considered razing the structure, but eventually decided to renovate and finish the castle by adding another wall, all four turrets, and 26 rooms for guests and staff. Today, the view from the castle stretches as far as the eye can see over hills that rise and fail like the swells of an ancient sea.

Less than an hour after our arrival, Scott and I noticed guide Sean Cochran and his client, Weston Willis of Abilene, pulling into the castle yard after their afternoon hunt. Towering above the back of their Polaris Ranger was a spectacular set of antlers, which that evening was scored at 255 inches SCI. Willis and the seven Gold Medal hunters who preceded us all took home racks that ranged from 221 to an incredible 301 SCI points.

Scott was already feeling like a kid on Christmas day, and the awesome size of Willis’ deer heightened his sense of anticipation even more. But first would come my chance to once again enjoy the fabulous bird-hunting at Greystone.

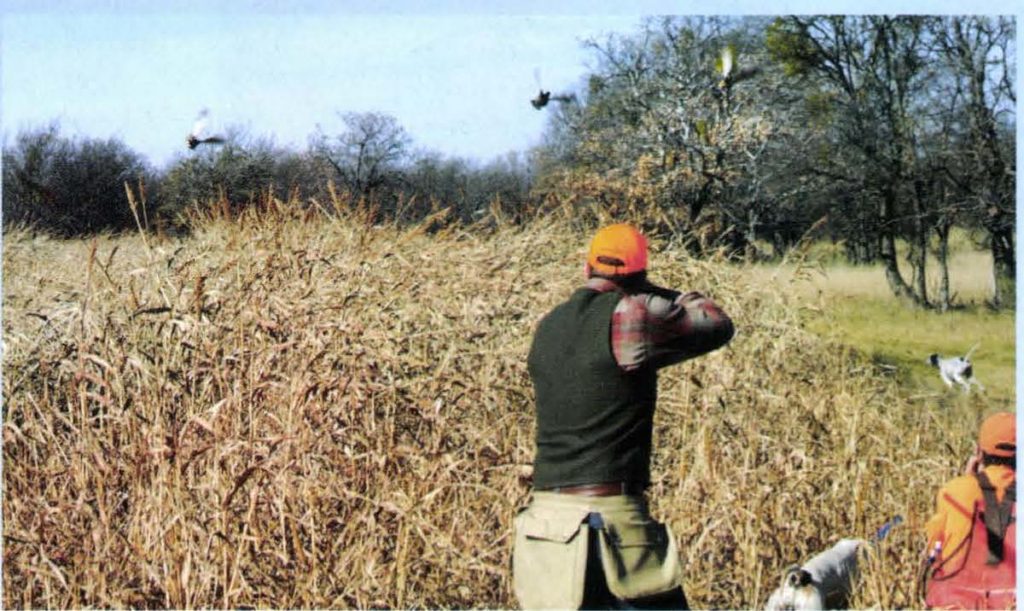

While Jennifer had touted a number of key changes at Greystone, our quail hunt that next morning was remarkably unchanged from what I had experienced years earlier. We even had the same guide, Tim Wright, who oversees the wingshooting while somehow finding the time to train and tend to the kennels’ 53 resident gundogs—setters, pointers, German shorthairs, English cockers, and Lab retrievers.

This hunt, however, was even more enjoyable because it included my good friend Clay Howard who had driven over from nearby Keller for our morning hunt. The day started out relatively cool but the weatherman had predicted a blistering 95 degrees by late afternoon, which would limit our hunt to roughly three hours before it became too hot for the dogs.

Tim led us down the first of many grassy strips where his pointers, Gunner and Bandit, gamboled in and out of the tall cover for some 200 yards before they stopped and pointed into the shade of a mesquite thicket. Tim released Elvis, his English cocker, and the little guy bobbed and bounced like a black rubber ball over and through the grass, quickly putting up a covey of some 12 birds.

All of us were impressed by the wildness of the bobwhites as they burst from cover and rocketed away. Screened by the trees, I couldn’t get a clear shot, but Clay and Scott combined for three birds.

A dozen more points and big covey flushes followed, each a blur of feathers as the big coveys sped off in all directions, their wings whistling through the still Texas air.

Clay was definitely up to the challenge with his Winchester Model 21. Twice he doubled on covey flushes with the little 20-bore, the last coming when he took a bird slanting off to his right and then dropped a hard-flying crosser that had flushed from the back side of the thicket.

Later that afternoon we gathered up our rifles for our first go at big game. Before heading out, my parting words to Scott were: “Be patient. You’ll most likely see a number of great bucks in the days to come, so don’t take the first big one that walks out.”

But that’s exactly what he did.

Gusty winds and 91 degrees-—seemingly the worst possible conditions for hunting whitetails greeted Sean and Scott as they settled into their stand overlooking a pasture girded by dense woods. About a half-hour before sunset a small herd of deer began drifting toward the feeder. First came a shooter buck with several broken tines, followed by two does, a spike buck and finally, just before sundown, a buck carrying a regal crown of tall, heavy antlers.

“I remembered what you told me about being patient, but his rack was so big , so impressive,” Scott said. “We watched him for about five minutes and every time he turned his head, I saw another point that I hadn’t seen before.

“I couldn’t not shoot . . . he was too beautiful. But my problem was that I was shaking so bad.”

Scott lowered his .270 Kimber, took a deep breath, and once again placed the crosshairs on the buck, which by now was poised in a moment of exquisite tension. One shot and suddenly Scott had felled his dream buck. Gnarly, massive and tall, the rack has 17 measurable tines and a 21-inch spread. Truly a spectacular trophy.

While Scott was admiring his giant buck, guide Lantz Horn and I were driving the maze of sand roads on the 1,500-acre exotics pasture, home to some 30 different species of wild game. Touring the pasture was like returning to the grassy savannahs and acacia woodlands of southern Africa, where years ago I had shot kudu, blesbok, gemsbok and several other varieties of antelope.

In a few hours we spotted all of these species, along with a number of others from various corners of the world. But of all these animals, the blackbucks were the wariest, hesitating only momentarily at the sight of our vehicle before racing away through the dense woodlands.

Toward sundown we arrived at the rim of a shale ridge where the road plummeted into a narrow, shadow-filled valley. Stopping on the deeply rutted road, we glassed two blackbucks in heated combat, their small hooves kicking up big clouds of dust as they lunged at each other wielding their pointed horns like rapiers. Both were mature males, but neither had the horn length and vivid black-and-white pelage that I was looking for.

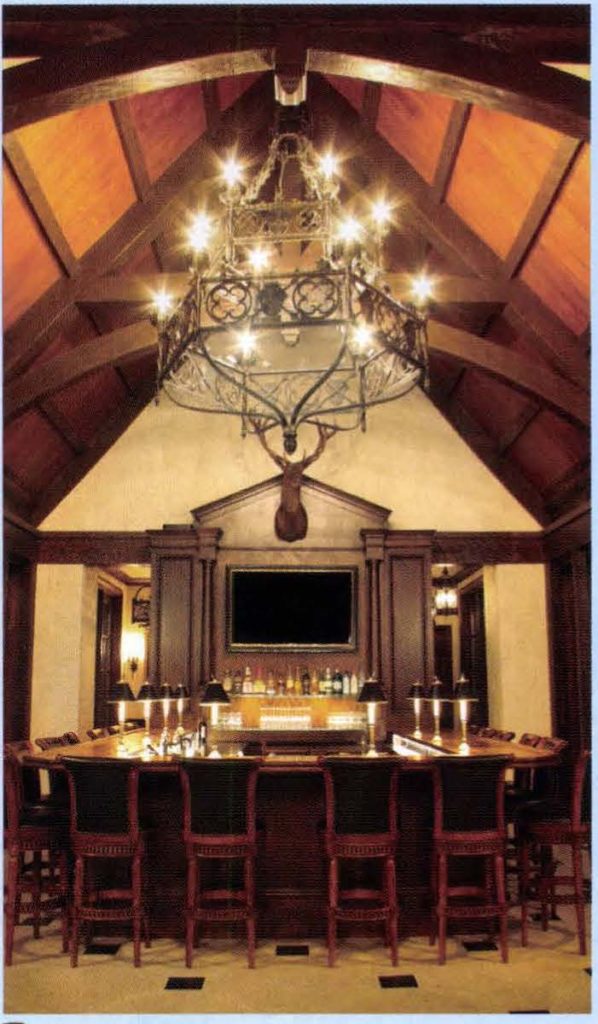

That evening we celebrated Scott’s trophy buck in the new 2,700-square-foot pavilion, a handsomely designed gathering place with a big horseshoe bar, lounge area, and game room complete with a pool table and electronic shooting game. After a round of drinks at the open bar and a delectable appetizer of Southern Style fried quail created by Chef Trey Zingelmann, we reassembled in the dining room for his pièce de résistance: Game Bird Potato Hash featuring smoked wild duck. Finally, moving markedly slower, we headed out to the big fire pit adjacent to the pavilion to relive our day’s adventures beneath a breathtaking galaxy of stars before turning in to dream of the next day’s hunt.

Daybreak was climbing the hills when Lantz spotted a male blackbuck and five does entering the wide meadow about 200 yards in front of our blind. The male blackbuck defines its territory, or lek, by depositing his feces in a series of small piles. As the morning sun cast its golden rays across the land, we watched the buck alternately grazing and urinating, occasionally glancing up to check out his harem.

The ebony patches on the male blackbuck grow even darker with age and as the animal becomes more dominant. The buck before us was almost pitch-black across his face and upper body, with his white eye patches and belly standing out in brilliant contrast.

We studied the buck through our spotting scope for nearly a half hour before I finally decided he was simply too good to pass up. After a single bullet from my Sauer .30-’06, we walked over to admire the beautiful little buck and his spiraling 18-inch horns. That afternoon Reserve Manager Greg Brummel gave us a tour of the biggest change yet at the Greystone.

Several years ago, the property’s two owners purchased a 900-acre tract just east of the castle where a l00-year-old lake had gradually filled in with silt. With a goal of creating an outstanding fly-fishing venue for bass and bream, they bulldozed a series of deep channels, using the spoil to build up two long berms that span most of the lake. The berms will serve primarily as earthen platforms for fly-casters, but they’ll also stop the hot Texas winds from whipping up waves on the lake.

“It’s interesting how rain can create big problems . .. or conversely, big benefits,” said Greg. “The basin was almost dry until last May, when the Dallas/Ft. Worth area received more than twenty inches of rain. We computed that over three hundred million gallons of water flowed into the basin and suddenly, we had our lake.”

Greg and his staff have already stocked its waters with 6,000 Camelot Belllargemouths, a fast-growing strain of Florida bass. They’ve also dumped in a quarter-million coppernose bluegills, a feisty, panfish that can reach two pounds or more in just a few years. Future plans call for introducing large mouths and hybrid bass into several other ponds on the property.

The back portion of the lake will be developed into a duck marsh, while the surrounding uplands are planted to native prairie grasses or manicured and seeded in big food plots—sunflowers for doves, and milo, millet, and wheat for the deer and gamebirds.

While driving back around the lake with the castle perched high above its western shore, I found myself reflecting on the changes at Greystone that I now realized had made a great sporting facility even more outstanding. It was then the thought came to me: “Even if it ain’t broke, innovative minds can make it better.”