Wild Country River Guides By Jim Casada

May 25, 2017

SCA Articles

SCA Articles

Wild Country River Guides, Inc.

Floating Through the Land of Extremes

By Jim Casada

Alaska is as near to Valhalla as a mortal fisherman will ever come. Vast areas of this immense state remain unsullied wilderness where wildlife abounds. It is, of course, the final frontier of the United States. Recognizing these special qualities and their appeal, husband and wife team Chip and Connie Marinella have created an Alaskan experience offering an exciting alternative to the standard lodge-based fishing trip.

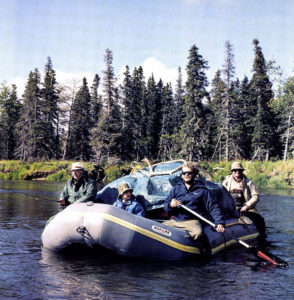

Their Wild Country River Guides, Inc. functions on the premise that one can enjoy marvelous and diverse fishing while simultaneously getting in touch with nature. They offer a view of the wilderness that is simply not possible under the daily fly-out arrangements normally associated with the lodges. Instead, there is the more rugged adventure, albeit in a pretty grand and luxurious fashion, of a week-long float trip on rivers in the Iliamna-Bristol Bay Region (three-day trips are also offered).

Art Carter of SportingClassics and I flew into Anchorage on August 19 and were warmly welcomed by Chip’s long-time assistant, Steve Ramsay. “Otter,” as Steve is fondly nicknamed, took us to Chip and Connie’s newly opened Orvis dealership, Angler’s Habitat, to meet the boss and procure our licenses. Chip and his staff carry ample quantities of effective lures, including flies of their own production, and they are knowledgeable about those that are likely to prove successful.

Art and I had all the personal gear we needed, thanks to a first- rate pre-trip infonnation kit Connie had sent to us. This detailed eight-pagelist, together with a questionnaire which is completed by each client, assured us of being well prepared for our stay. We were thankful by the trip‘s end that we had adhered to the kit’s practical advice. Our Gortex rain gear, stocking foot waders, and carefully selected clothing enabled us to withstand Alaska‘s climatic rigors.

By the time we had acquired our licenses, Chip had returned from some last-minute shopping to escort us to his home. There we met his wife, Connie, and spent some pleasant hours talking to the couple over drinks and hors d’oeuvres. Finally, we said good night to C hip and Connie and retired to our night‘s lodgings, the International Inn on Lake Hood, the world’s largest float plane base.

We were up early the next morning, anxious to meet our trip companions at the airport and to board the small passenger craft that would take us to Iliamna, our float-plane connecting point. Even our first dose of”Alaskan sunshine,” the locals’ name for rainfall, could not dampen our enthusiasm.

At the flight gate we met our traveling companions. They included C hip‘s accountant, Ray Grundhauser, together with his son, Hans, and father–in–law, Kenny Blanton. Louis, a local acquaintance of Ray’s who had decided to join the party at the last minute, completed the group. Ours was a full booking; six clients are the maximum number accepted for any float trip. With three guides, this insures each individual ample attention and fishing opportunities.

We were quite a mixed group in terms of previous outdoor experience and fishing background. The trip was a first for Ray and Hans; Kenny proved a tried and tested camper whose energy and enthusiasm belied his years, and Art and I, inveterate fly fishermen, discovered that we were in the company of four spinning enthusiasts. Under other circumstances this blend of purists and spin–plunkers might have proved disastrous; however, Chip and his guides, whom we were to meet at the float plane drop-off point, adjusted to our varying degrees of expertise and differing fishing interests in a manner that attests to their flexibility and professionalism.

During the flight to Iliamna aboard a 12-seat Beechcraft, we saw glaciers and snowcapped peaks nestled amid broken clouds, with visibility in the incredibly pure air extending to 85 miles. At one point we were squarely between Mount Iliamna and Mount Reno, both of which rise to over 10,000 feet, and Cook Bay was visible in the distance. Iliamna is little more than a village entrepot to the Bristol Bay region, and Art and I, with most of the party’s gear, flew out first after we had repacked everything in waterproof bags from Chip‘s storeroom there.

Upon landing (our touchdown on what seemed an impossibly small lake proved why Alaska’s bush pilots are considered the world‘s best), we met Chip‘s youthful but skilled assistant guides, his 21-year-old cousin, Mike Scarano, and 24-year-old Greg Dudgeon. Both had taken a week off from guiding duties to hunt caribou, and they had two fine racks and a load of meat awaiting the bush pilot‘s return trip to Iliamna.

While we waited for the rest of the group, G reg and Mike transported our gear across the mile and a half of tundra to the river with a cart pulled by a sturdy three-wheel motorbike. Meanwhile, Art and I spied a caribou only a few hundred yards away, and Art was immediately off in pursuit with camera in hand. Thanks to some adroit stalking and the caribou‘s amazing lack of fear, Arttook some pictures at a range ofonly50 feet. As I observed the action from the tundra moss, a brace of ducks flew overhead 0 low that I could have almost touched them. It was a memorable opening to our trip.

By mid-afternoon the remainder of our group was on the ground, and we took off. We were to float the Stuyahok River from near its headwaters to its juncture with the Mulchatma on two large rafts, one equipped with a rowing frame and a large aluminum storage chest. There was no fishing the first evening since we had started late and still had to row for several hours before reaching Wi llow Camp. This first night we were still in tundra country, and as Chip prepared dinnerand Mike and Greg set up camp,thewindbegantorise. Itcarriedthepromiseofrain.

Our dinner at Willow Camp, as would be the case with every succeeding sit–down meal (we lunched while afloat or between fishing excursions), was one of the high spots of the trip.

Breakfasts included old standbys such as eggs, bacon, ham, and toast, but there was always an imaginative touch– fried Dolly Varden trout or French toast with a touch of cinnamon and coffee with an irresistible aroma.

It was the evening meals, however, that truly gave credit to Chip‘s culinary talent. Mixed nuts, raw vegetables with ranch dip, smoked salmon, and similar delicacies started us off each night. Among the main courses were T bone steaks with all the trimmings, Oriental night with marinated pork cutlets rounded off by stir–fried vegetables and brandied peaches, bbq ribs, fried chicken,and seemingly inexhaustible quantities of steak and Alaskan king crab. Wine accompanied all dinners. My favorite was Italian night: minestrone, spaghetti with a tasty homemade sauce, and garlic bread. Just before serving the meal, Chip and Mike appeared in authentic Italian costumes replete with taped Italian music. From the very first night, dinner became an occasion everyone awaited with keen anticipation. Indeed, I can truly state that in a lifetime spiced by countless camping trips, I have never eaten better.

That night the elements unleashed themselves with a fury that would bombard us almost relentlessly throughout the trip. Scarcely had we settled into our sleeping bags atop cots when it began to rainhard. Thedownpourcontinuedthroughoutthenightasthe wind rose to near gale force. Nonetheless, we slept, well fed and exhausted. Fortunately with the dawn the rain eased off to a steady drizzle. The stonn had been sufficient to break beaver dams upstream, and this combined with the continued rain kept the river high and dingy throughout the trip. Such conditions are not conducive to flyfishing, but Iwas heartened bya pre-breakfast rainbow of about two pounds which I caught on a garish tinsel fly appropriately known as a “Christmas tree.”

The rain continued to affect fishing adversely, but even under circumstances which the guides assured us were the worst of the season, the river produced some bright moments, especially while we were at Caribou Camp, our destination on the second day’s float. En route we noted striking changes in the landscape as we made the transition from tundra to rugged forest country. We stayed at our second campsite for two days and experienced the best fishing of the trip. I caught a rainbow in the four to five pound range during a stopover on the way to Caribou Camp, and Art took its twin in the shadow of Caribou Mountain the next day. The two fish would prove to be the only sizeable rainbows taken in the course of the entire trip, although we did catch a few others in the 14 to 16-inch range.

After settling into a new camp, Art and I spent several hours together n the stream. Here, for one glorious evening, we encountered Alaskan fishing as it should be. Plying the “babines” (a double salmon egg imitator pattern with a hint of white to represent spern1) recommended by Greg, the two of us caught upwards of 20 fish in a relatively short time. The variety was impressive. We took and released rainbow and Dolly Varden trout, the ubiquitous Arctic greyling (Art would, before the trip’s end, refer to them in a semi-disparaging manner as “Arctic carp”), and for the first time our most coveted quarry, silver salmon.

Both of us took nice Dolly Varden, welcome additions to breakfast next morning, and Art very nearly wore down a silver salmon that likely would have gone 17 or 18 pounds if the hook hadn’t pulled out in the struggle. The silvers were still very strong even though they were vivid red, which indicates the later portions of their spawning run. Some we took were spectacularly acrobatic. Between us we caught a dozen or so salmon that evening, probably losing twice that number, and there was the added fascination of never knowing what type of fish the next strike would bring. As dusk approached (and the long days of the Alaskan summer mean this is quite late in the evening), Art hooked and landed a silver that we judged to be in the 13 to 15 pound range. After we had released it both of us left the stream highly pleased, certain that the days to follow would produce comparable or even better fishing.

We should have known better, as any time-tested angler can attest. That night and the next day the rains, which had never completely stopped, returned with a vengeance. As the water rose and became increasingly murky, the quality of fly fishing declined dramatically. I did manage to take a salmon in the same size range as Art’s silver of the previous evening, and its six jumps in the course of a 20-minute fight were glorious to behold. These, however, proved to be the two largest fish of the entire trip, and with each passing hour strike were more difficult to come by. Even our spin-fishing comrades had problems, although Kenny’s persistence resulted in the float’s only char and a good number of silvers. Both Ray and Hans took enough fish to keep them happy, but the guides woefully acknowledged that the elements had conspired to produce the worst week of the season.

Even so, it is clear that the float trip, under normal circumstances, can produce outstanding fishing. Early in the season, for instance, fishing for king and red salmon had been exceptional. However, the nature of the trip is such that angling is only one of a number of pleasing features. Indeed, it could be the experience of a lifetime even for a non-fisherman, and Ray and Hans’s enjoyment shows that the fishing can be as enjoyable for the novice as for the seasoned sportsman.

As regards equipment, the information supplied in advance by Wild Country River Guides covers pretty much everything one should know. For the fly fisherman, two good quality rods, one in a six or seven weight and a second, heavier rod (I would suggest a nine weight) for salmon, together with accessories, should be adequate. One item that was unavailable was a landing net, and both Art and I wished for a small collapsible one which would allow us to land and release fish as gently as possible. While there reportedly are times during the season when dry flies produce, success is more likely when streamers or flies are fished near the bottom. A line with a fast sinking tip or the use of some lead core spliced in is essential to get the lure down to the fish quickly. The fish are not leader shy, and we found that a quite short one tapering to eight pounds was completely satisfactory. What is of paramount importance is getting the fly to the fish and making the method of presentation convincing. Wading skill and proper wading equipment are also important, especially given the unusually high water we faced. For spinner fishermen, various types of Mepps (with two of the treble hooks clipped, as this is trophy water where only single-hook artificials are allowed) seemed to work well.

While strong salmon and the free striking grayling were quite a contrast to the small rainbows and browns Art and I are accustomed to taking in the streams of the southern Appalachians, other aspects of the trip impressed us more. On any outing of this type there will be memorable experiences, often ones to be treasured for years to come. We found Chip, Greg, and Mike not only competent, hardworking guides, but also warn, engaging individuals. lights around the campfire, following a good dinner with plenty of food and wine, brought challenging conversation, the topics ranging from the verse of Robert Service, the poet of the Yukon, to the trials and tribulations of outdoor editing and writing. We may not have solved many problems, but our free- ranging, raucous discussions gave all of us a sense of shared fellowship.

Our guides’ personalities complemented one another nicely. Greg’s quiet, thoughtful demeanor contrasted perfectly with the quintessentially Italian liveliness of Chip and Mike, and the love each has for the outdoors was infectious. They were old hands at this vocation, yet one sensed that constant exposure to Alaska had done nothing to dull its luster for them. Certainly the rest of us saw awe-inspiring sights daily. We saw eagles during our second day on the river, and during the float between Caribou and Otter Camps we saw more. At one point Art took some close-up photographs of a fledgling eagle perched on the nest in a solitary spruce. Families of ducks constantly played tag with the rafts while ospreys and other hawks sporadically appeared overhead.

More impressive, though, was the sudden appearance of four caribou while we were at Caribou Camp. Outlined against the mountain which rose for several hundred feet from the river’s opposite bank, they somehow conveyed the essence of this pristine wilderness setting. Two of the caribou carried massive racks, and their almost casual entrance on the scene served to remind us that we were little more than passing interlopers in their world. Bear sign was everywhere, showing that the grizzlies were feasting on dying or rotting sockeyes and the ample quantities of available berries. Fortunately we had no serious encounters, although a bear already known to the guides from previous trips did appear just outside camp one evening. The guides were always alert for and respectful of the bears–and their sensible precautions gave all of us a needed sense of security.

Alaska is a land of extremes, climatically and otherwise. By the time we reached Moose Camp on the penultimate day of our trip, we noticed that the vegetation and terrain contrasted sharply with the tundra region in which we had begun. That day the weather, as if to remind us of its unpredictability, cleared to reveal azure skies. With nightfall the heavens overflowed with more stars than it seemed possible for them to hold. A distinctly autumnal chill replaced the mist and rain that were by now old acquaintances, and by sunrise the mercury was hovering at 30 degrees which felt even colder in a brisk breeze. Nonetheless, we welcomed the change.

We broke from Moose Camp fairly early to meet the bush pilots at the river’s mouth, and my final fishing efforts, as well as Kenny’s, were rewarded with a small salmon apiece. When we reached the sweeping Mulcharna River, however, I was not thinking about fishing. As we waited for the plane, my thoughts turned to two lasting impressions.

One was a fleeting glimpse which I had caught early in the morning at our final campsite. Walking quietly to the river, I spotted an osprey soaring into the distance, its talons clutching a fish freshly caught for breakfast. Second, and even more moving, was the wonder of a week afield without sighting any of the vestiges of civilization. Not once, in the entire course of our float, had we seen a can, plastic wrapper, bottle or paper, and that seemed to me a true hallmark of wild country. Our experience had been one any lover of all that is nature’s finest would cherish for a lifetime.