Fall Float on the Wild Watauga

October 15, 2020

Fishing,SCA Articles

Fishing,SCA Articles

For late-fall tailwater fishing, my favorite is the Watauga. Thirty to 40 fish catches are not at all uncommon.

Ok. I should have sheathed my fly rods and unlimbered my shotguns by now. Doves have been flying for a couple of months, that 20-gauge double just itches for grouse, and preserve hunts for quail and pheasants abound in my neck of the woods. Most anglers have forsaken streams draining the southern Blue Ridge. Flows are so low and warm, and brookies and browns are spawning. It’s more than a shame to stress them further. It’s nothing short of criminal.

So what’s a fly flinger to do? Head for the nearest tailwater and float it.

I’m blessed with a trio of high-quality coldwater outflows within an hour’s drive of Asheville. There’s the Nantahala, known for kayaking and whitewater rafting, which the river’s big browns and ’bows don’t seem to mind. The Nan brawls its way down a tight valley, careening through chutes into pools and short stretches of pocket water. During releases, it can be a bear to wade.

Chilly releases from TVA’s South Holston and Watauga Dams bring water temps down into the range so highly favored by trout. But when generation stops the current is truly benign. Renowned for leviathan browns, public access on the SoHo for wading is scant, and two spawning runs of the river are closed from November 1 to February 1. To reach excellent sections, fish the rights-of-way where TVA transmission lines cross the river.

While the SoHo may produce more big fish, for late-fall tailwater fishing, my favorite is the Watauga. Thirty to 40 fish catches are not at all uncommon.

Browns predominate among Watauga’s wild rainbows and brookies.

Fly fishing for late-fall trout begins where the river exits Wilbur Dam southeast of Elizabethton, Tennessee. Above Bee Cliffs, this water delights whitewater enthusiasts. Below the rapids, the river runs for about 15 miles across outcrops and gravel beds. Many floats begin at Siam (Yep) and take out at Elizabethton. Others launch in this old industrial town and drift through Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency-designated 2.6-mile “Quality Waters.”

A couple of weeks ago, my brother Sam and I floated a section of about four miles from Hunter Bridge to Riverside Park in Elizabethton. The trip was a special birthday present for Sam. He and I had fished the river often while students (I use that term very loosely) at East Tennessee State University in the late 1960s. We hurled Mepps and Panther Martins and dunked Pautzke’s red Balls O’Fire salmon eggs and wasp larva with our ultra-light spinning gear. We were delighted with limits of flaccid stocked rainbows. Sometimes wild browns struck our hardware. I can still see the fist-sized head of the huge brown that took my Mepps, fought me for what seemed an hour, and spit the hook just as I was about to net it.

Known for its summer hatches of blue-winged olives, you’ll see occasional midges coming off the Watauga in late fall. Though I much prefer fishing dries, nymphs are the name of the game when leaves crisp and begin to turn. Guide Matt Champion of South Holston River Fly Shop all but insisted that we toss a #16 olive trailed by a #22 midge dropper beneath a bright-orange strike indicator. He added two micro-shots to get the brace of flies down to where the fish would lie.

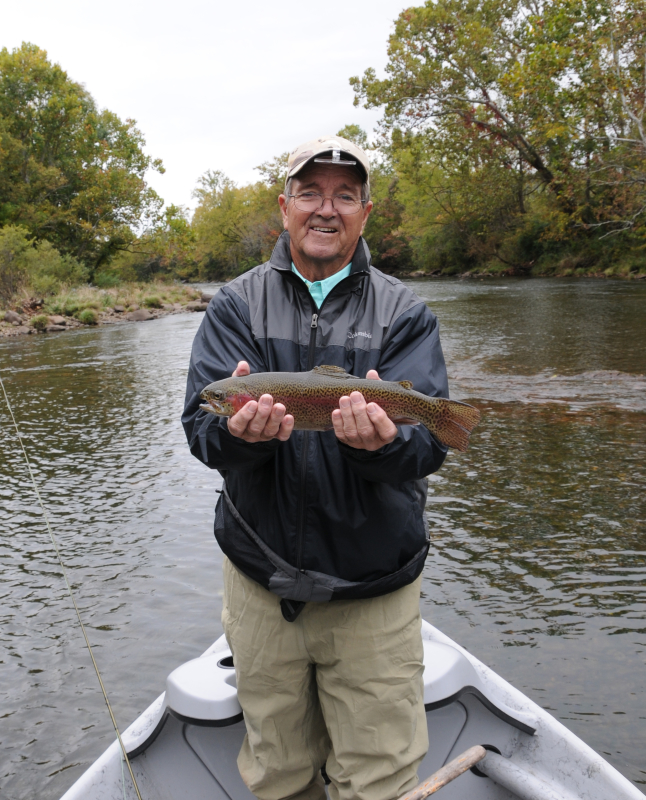

The author’s brother took one of Watauga’s 14-inch rainbows on a #22 midge nymph.

On a previous trip with guide John Stunkard, I’d cast the twin-nymph rig just upstream of a downed log along the bank. It wasn’t a long cast, only about 50 feet. Moments after it hit the water, a lovely brown rolled and took one of the flies, which one I’ll never know. All I saw were black specks on its dorsal fin and back, which seemed more than a foot long. All I felt was a very soft bump, then a twitch and he was gone.

We guessed he’d hit the #22 dropper and the hook had failed to lodge in its jaw. Later, on the same float, a beautiful 16-inch wild rainbow struck the upper nymph, spit it out, and got itself hooked in the anal vent with the dropper. What a fight! First it ran upstream stripping line from my Pflueger Medalist reel. Next it reversed course and raced downstream, streaking by the drift boat as I reeled as fast as I could to take up slack. Its flight nearly doubled my old six-weight Orvis bamboo rod. I’m certain that only the rod’s suppleness protected my 6X tippet.

That ’bow hit the flies in a fast little chute between a pair of boulders—That’s the kind of water were Sam and I caught most of our fish. They weren’t huge, averaging about 11 inches. Most were deeply colored and likely progeny spawned in the river. Short casts, seldom longer than 30 feet, up and into the head of rapids were most productive. Much as I hate strike indicators—reminds me of bobbers for bait—they’re all but essential when fishing for Watauga’s late-season tailwater trout.

Wild rainbows turn rapacious with the coming of fall.

I’d booked a half-day float. During our five hours or so on the river, we caught and released about 30 trout. Along the way we jumped hordes of Canada geese, flushed a few mallards, and were roundly cursed by kingfishers. The last of late summer’s purple asters and early fall goldenrod spiced the banks. The river flowed dark, cold, and clear like iced tea. Trout seemed to hit better when the sun was out, and cloud shade failed to trigger the midge or blue-wing hatches for which my four-weight was rigged with a dry.

Although this section of river can be waded easily, public access is basically limited to bridge crossings. The best way to fish it is to float it. Anglers like me, whose tailbone seems to be succumbing to the vagaries of age which make wading a bit challenging, will find a drift just like this perfect medicine for early fall.