Arapaima Dreamin’

March 2, 2020

SCA Articles

SCA Articles

Deep in the jungles of Guyana, they caught giant arapaima on the fly while dodging caiman, jaguars and the dreaded water anteater.

For many fly fishermen, modern-day angling is a genuine global pursuit and not just for trout. Most any gamefish in the sea or in freshwater is a target these days – and space-age tackle helps make fighting big, exotic fish a little bit easier. Travel agencies that cater to fly anglers help eliminate some of the hassle of getting to and from far-flung waters. So, if you’re a globetrotting angler or want to be, these are the glory days.

Most angling travel centers around one of the salmonids – Pacific or Atlantic salmon, various species of trout or taimen – but fish of goliath sizes are sprinkled across several continents and speak to anglers who crave adventure and huge fish. Africa has Nile perch, Asia has mahseer and South America has arapaima. Access to these big fish is not easy, and catching them on the fly is even more difficult.

Of these three species, arapaima is the largest, and in the spring of 2012 I heard about some recent exploration into the jungles of Guyana to establish an angling destination for them. Soon I was on the phone with Oliver White, a Bahamian bonefish lodge operator and promoter of the Rewa River and its huge arapaima. White had indeed booked three parties each with four anglers. One of the groups, however, had to cancel for the opening week.

My longtime angling buddy, Gary Aka, and I jumped at the chance to be the first anglers on the Rewa. We were happy to learn the camp would be run by an American, Matt Breuer, who was also general manager of Ryabaga Camp on Russia’s Kola Peninsula, one of the premier Atlantic salmon destinations in the world. Breuer had been an angler on the exploratory trips to the Rewa and had caught four arapaima on a fly rod making him the most experienced arapaima fly fisherman in the world.

Gary and I met Matt in the Miami airport, and we shared Thanksgiving dinner before our flight to Georgetown. From there we took a two-hour charter that ended on a grass landing ship in the town of Apoteri, which is near the center of Guyana. Next came a short trip by motorboat up the Rewa River.

I scanned the water for glimpses of our legendary arapaima and the banks for sight of the elusive jaguar. Ninety minutes later we settled into our spartan but comfortable quarters at the Rewa Village Eco-Lodge. I had left my home in Reno two and a half days prior. Though the jungle held dangers known and unknown, and fishing waters are always a mystery, we were thinking solely of arapaima as we hurriedly prepared our gear for an afternoon of fishing.

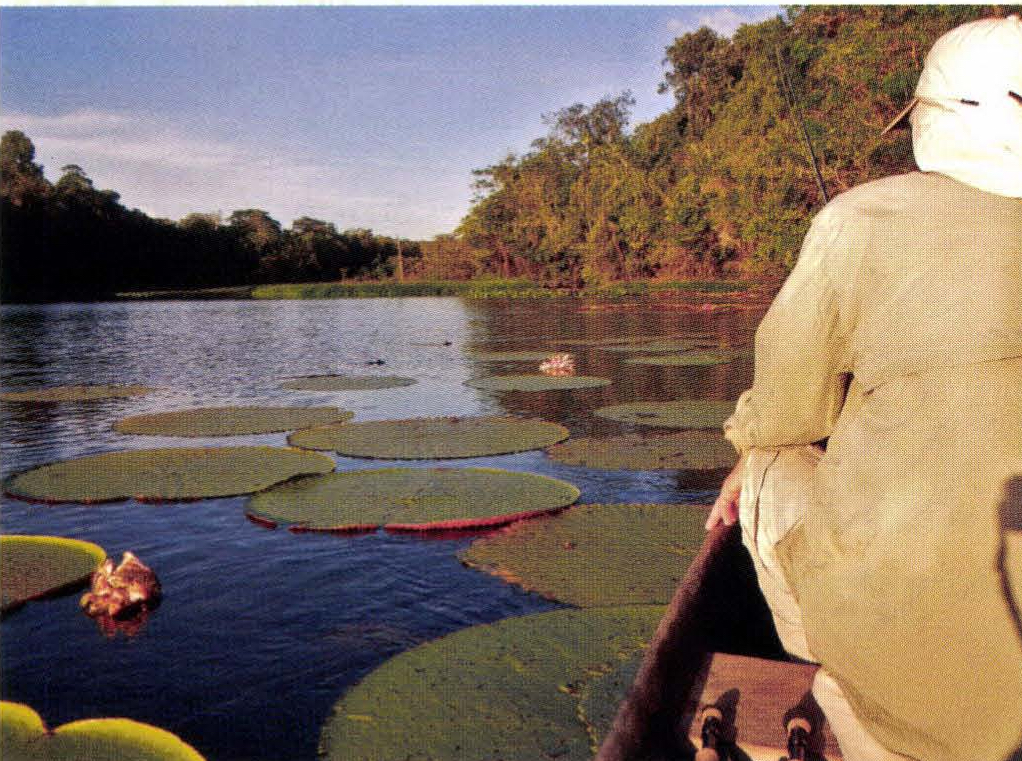

Only four hours of daylight remained as we left Rewa Village with our two Indian guides, Rovin and Dennis Alvin. There are four tribes in Rewa Village and the Alvin brothers belong to the largest – the Macushi. While they still like to hunt with bows and arrows, and carve their canoe paddles out of purple heartwood, they are skilled operators of outboards. They motored us upriver to a jungle trail that led to Brantash Pond, one of many jungle lagoons, where Gary and I each boarded a dugout canoe.

During the wet season, the Rewa rises out of its banks, and many of the river’s denizens, including arapaima, leave the main flow and literally swim through the jungle. As the flooding abates, many fish return to the Rewa but others remain trapped in lagoons left behind by the receding waters. The shallower lagoons dry up, but larger and deeper ponds persist year-round and support thriving fisheries with hundreds of species, including several varieties of piranha and sporting favorites such as peacock bass – and arapaima.

The arapaima is the behemoth of South American freshwater fish. It can attain a length of more than ten feet and weigh several hundred pounds. Given such size and strength, we planned to use our 12-weight fly tackle. Gary had tied some eight- to ten-inch imitations of juvenile peacock bass in both greens and browns on 8/0 Tiemco hooks. Oliver had advised us to bring floating, intermediate and sinking fly lines so we could adjust to different water depths. He suggested at least two of each line, since we were likely to lose gear to piranhas.

The leaders were like nothing I’d ever seen. We began with an 80-pound-test butt section looped to a short piece of 40-pound mono that served as the weak link in the event we needed to break the line. The leader terminated with an 80-pound-test shock tippet to which we tied the fly. We certainly did not expect the fish to be leader-shy.

Rovin advised us that the speed of our retrieve would be crucial. Arapaima are not prone to chasing a fly that’s zipping through the water similar to escaping prey. He suggested a couple of slow, six-inch strips and then a pause.

Rovin began looking for rolling fish that were within casting range (similar to tarpon, arapaima rise periodically to gulp air). He told us to lead our target by about five feet, then before stripping, pause long enough to let the fly sink to the bottom.

That afternoon in Brantash Pond I had my first glimpse of the holy grail. I froze on the bow, afraid any movement would spook the magnificent creature that was within 15 feet and suspended so high in the water column that its dorsal fin created a tiny ripple. I could practically count the huge, orange-tinted scales along its five-foot torpedo-shaped body. The head and tail were nearly as thick as the midriff.

My excitement waned as the big fish slowly sank out of sight, clearly wise to its intruders. But that afternoon Gary and I had a few casts at rolling arapaima, and I had one fish wake after the fly.

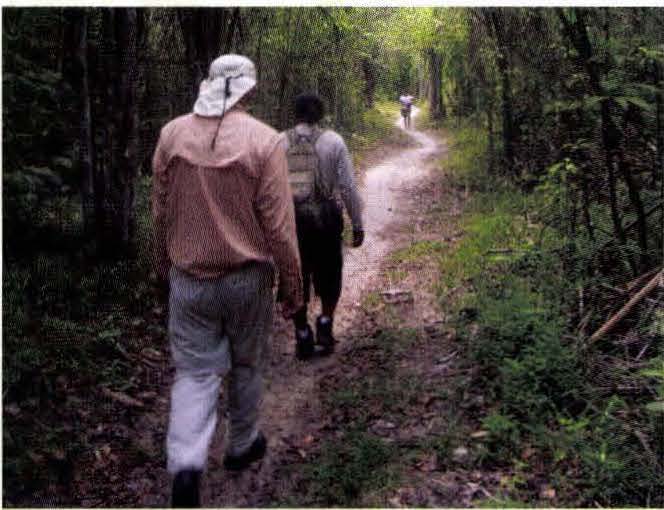

The sheer excitement of seeing such huge fish carried us eagerly to the next morning, when we hiked to Grass Pond, where I would fish with Matt and Dennis, while Gary went with Rovin. It was an easy stroll, less than a half-mile, on a cleared trail through a surprisingly thin understory. No monkeys howled and no birds sang, but our guides were so enervated that I expected them to burst into song at any minute. They clearly enjoyed their work.

Within the hour at the shallow end of one branch, we were casting steadily to rolling fish in a veritable tropical garden. Blooming water hyacinth lined both shores, the white splash broken occasionally by the phallic buds and beautiful blossoms of the giant Victoria amazonica water lily, Guyana’s national flower. The water was clear enough to see a few of the bottom-lurking arapaima, though it was difficult to determine which end was the mouth or tail.

I must have cast to ten fish before getting a solid hookup. With a hard strip-strike, I buried the hook but hit it a couple more times to make sure. Matt immediately began photographing my 20-pound “trophy.” It was about as small as arapaima come, but it was my first and it was great. Besides, the day was young.

A few casts later my sub-surface retrieve stopped suddenly as if the fly had snagged on a log. But then the line started moving off slowly, and I was into something really big. Gary, meanwhile, who was about a hundred yards away, hooked a big arapaima that jumped several times. Both guides paddled the canoes into the shallows where they could get in the water to release the fish. My catch was almost impossible to move but came along grudgingly.

Matt joked about the first arapaima double in fly fishing history, but as we grew closer to shore, the ugly head of an enormous black caiman broke the surface with my fly embedded just behind its right ear. The huge reptile glared at us malevolently and then sank below the surface. Matt broke it off by wrapping both hands around the fly line and giving it all he had. Thank goodness for the 40-pound section of leader.

Rovin estimated Gary’s fish at 180 pounds. The fight, which had lasted more than a half-hour, was highlighted by several spectacular leaps. And later in the day I hooked and lost a large arapaima before landing a 30-pounder.

That night, lying on a bed within the cocoon of a mosquito net, I struggled to fall asleep, still awash in the day’s memories and energized with exquisite anticipation.

The next morning, we motored upriver about 90 minutes and hiked a quarter-mile into Kumaka Pond where five villagers awaited us with two small aluminum skiffs. The trail was littered every few feet with small branches, which the locals had used as rollers for pushing and pulling the boats from the river to the pond.

The morning’s fishing was exciting yet frustrating. I fought one huge fish for 15 minutes, and the battle included several jumps that gave us good looks at its size. Rovin estimated its weight at 250 pounds. The tug of war was fierce but just as the arapaima seemed to be tiring and coming to the boat, my line went limp, neatly severed by the razor-sharp teeth of a piranha.

Noontime meant an excellent shore lunch before the serious business of napping in hammocks that had been strung between trees by the faithful five. With temperatures in the 90s, the fishing is slowest in the middle of the day, but the forest shade made for comfortable dozing.

The forest itself proved soporific, with its dreamlike flora and fauna – a blue morpho butterfly against the backdrop of dense vegetation that displayed every possible shade of green on the painter’s palette and soaring palms that appeared to be suspended from the cerulean sky by their fronds.

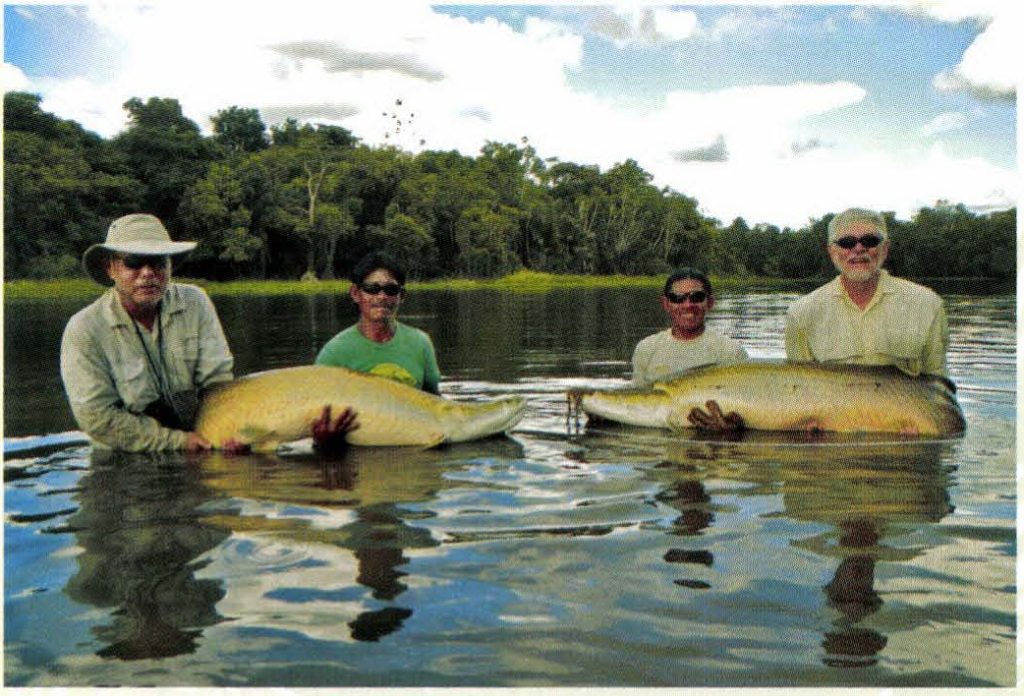

Shortly after lunch I hooked and lost another big fish. Then, late in the day, I stuck a monster and managed to land it after a 25-minute fight. The strength and violent shaking of this unbelievable fish inspired sheer awe. When I brought it alongside, Rovin prodded it with a pole and the fish ran off about 20 yards of line. I brought it back again. The prodding was repeated four or five times until the arapaima was on its side beside the boat. Prior to exhaustion, the fish would have been far too dangerous for anyone to be in the water with it – it could easily break someone’s leg.

The other boat came alongside, it took four of us to lift the beast just partway out of the water for the photos. Rovin estimated its weight at 300 pounds. It was easily the largest arapaima ever caught on a fly.

Later in the week, while fishing Grass Pond, Gary and I both hooked fish simultaneously and landed them together. It was arapaima fly-fishing’s first double -minus the caiman – duly recorded by Matt on his video camera. Gary’s fish was about 100 pounds and mine was twice as large. Just before dusk Gary landed his own 200-pounder and we headed back to camp.

On the way, Rovin pointed out a huge caiman swimming along shore with something in its mouth, perhaps a duck or wading bird of some kind. Gary wanted a photo, so we approached the predator and it quickly submerged. The water was quite shallow and the caiman left a clear trail of bubbles before resurfacing. When it saw us, it dropped its prey and dove again.

We immediately recognized Gary’s arapaima from our earlier double. The hundred-pounder was missing some scales after its journey in the caiman’s mouth, but when Rovin grabbed it, the fish began to twitch. Good grief … it was still alive!

Rovin jumped into the three-foot-deep water and began reviving the disoriented fish. After about 20 minutes, it started gulping air and straining to be released. On our last full day of angling, we traveled downriver to Blackwater Pond, where the Rewa committee of five again awaited us patiently, having already dragged the two skiffs into the interior. We followed the jungle trail into the pond, which is named for its dark, tannin-stained waters. This area is not without danger. A jaguar had been sighted there recently and the lagoon was also home to anacondas. Blackwater Pond is also the lair of the feared giant water anteater, a mythical creature with malevolent and supernatural powers.

Several years ago a villager and his wife were canoeing on the pond when the dugout began whirling in circles to the point that it was about to sink in its own vortex. About that time, a man noticed the huge claws of the water anteater on the gunwale and whacked it hard with his paddle. The creature gave the craft a shove that drove it all the way up on shore. Most natives now avoid Blackwater Pond.

Rovin warned us to be careful not to drop any pepper from our sandwiches into the water because even the tiniest amount would irritate the water anteater. He then opened a bottle of rum and poured three ablutions into the pond as an offering, a procedure he repeated when we returned to angling after our shore lunch. About an hour of daylight remained when Rovin decided to head back. Neither he nor Dennis wished to be on Blackwater at dusk, and the five bearers clearly wanted to haul the boats out before nightfall.

As we started upriver it began raining, accompanied by lightning and thunder. Rewa Village experienced a torrential downpour, and even before we arrived, word had spread that the storm had been sent as punishment by the water anteater, angered by our impertinence.

We planned to fish the entire morning of our travel day, and not surprisingly, Rovin opted for nearby Grass Pond. By nine o’clock I had fought three fish and landed a 200-pounder. Gary then fought and landed another fish of roughly the same size. Arapaima were still rolling all around us, but we’d had enough – indeed much more than our share – so we decided to tour Rewa Village instead.

I traveled to Rewa Eco-Lodge in Guyana with the hope of casting to a few arapaima but with no real expectation of catching one. My impossible dream was to land one fish, no matter its size. I now realize that for this briefest of moments, that I have probably caught the most and biggest arapaima of any fly fisherman – ever.

I am not a competitive angler. I have never entered a fishing tournament nor have I submitted a catch as a possible record. In fact, I consider myself to be a Zen angler, taking my fishing far too seriously to turn it into some sort of contest. However, I am aware that we have now established the historical baseline as far as fly fishing for arapaima is concerned.

Matt and Rovin compared their notes regarding the lodge’s fishing history and determined that, prior to our week, there had been 12 fly-caught arapaima at Rewa, including Matt’s four. Gary and I hooked 32 fish and landed 11. In short, we had just about doubled Rewa’s total catch.

I know that my “records” will be eclipsed and probably quite soon by Matt, other anglers or possibly Gary and I, as we are planning a return to Rewa next season. And as other arapaima destinations open, catch numbers will soar. Tight lines to all. I salute you as I sip my Chivas Regal and bask in the afterglow of what proved to be the most amazing week of my four-decade angling career. —William A. Douglass