A Prairie Boy In Paradise

November 6, 2018

SCA Articles

SCA Articles

When you’re growing up on the vast, eternal Dakota prairie and reading Jack London, you get ideas. Like spruce forests and white mountains so near the north end of the earth you can see the horizon curving off both sides. Caribou blowing steam, almost translucent in a fog of their own body heat. Moose trotting, kicking up silent snow. Wolves howling. These images become fixed, then prophetic as the prairie shrinks under the weight of years and you realize you must go see your dream wilderness. It isn’t there, of course. No one mushes sled dogs up the Alaska Highway, no one fights off wolves with burning brands. What took the prairies is taking the North, too. From the highways you see great squares of timber missing from the mountainsides, tangled stumps beside the way. At 90 kilometers per hour you’re clubbed with the Texas stench of oilfield that lingers in the cab long after you’ve passed the pump and well. From the air you see the black spruce forests cut with long wounds, perfectly straight investigations for mineral plunder crisscrossing the forests nearly to the hump of the white mountains.

But the mountains themselves — there’s the refuge of your dream. They rise in northern British Columbia like a great, cold island of wild indifference.

As we flew into this wilderness last October, the sun was setting behind the Continental Divide, slivers of its fire coloring scattered clouds and reflecting in the tattered ribbon of the Sikanni Chief River. A bull elk followed several cows up a dry foothill. Farther up the valley a hump of granite mountain broke in a sheer wall that plunged 1,500 feet into a deep gorge where the river roared over a falls.

Glacial lakes lie like emeralds on the mountain flanks, and in the high valleys, moose stood in silver pools. At the end of one pond was a tiny, yellow airstrip cut from the dark willow-flat surrounding it. Mud whirled off the plane’s tires as we touched down, bounced over a hummock, touched again, bounced and thus proceeded to a cluster of buildings beside the lake. Bluebell Camp. Moose camp. The mountain of bare rock that gave this camp its name rose to 8,000 feet behind our snug, sleeping cabins and reflected the first rays of morning sun. Each log cabin had a propane lamp, wash basin, wood- burning stove and two plank-bunks topped with thick foam pads.

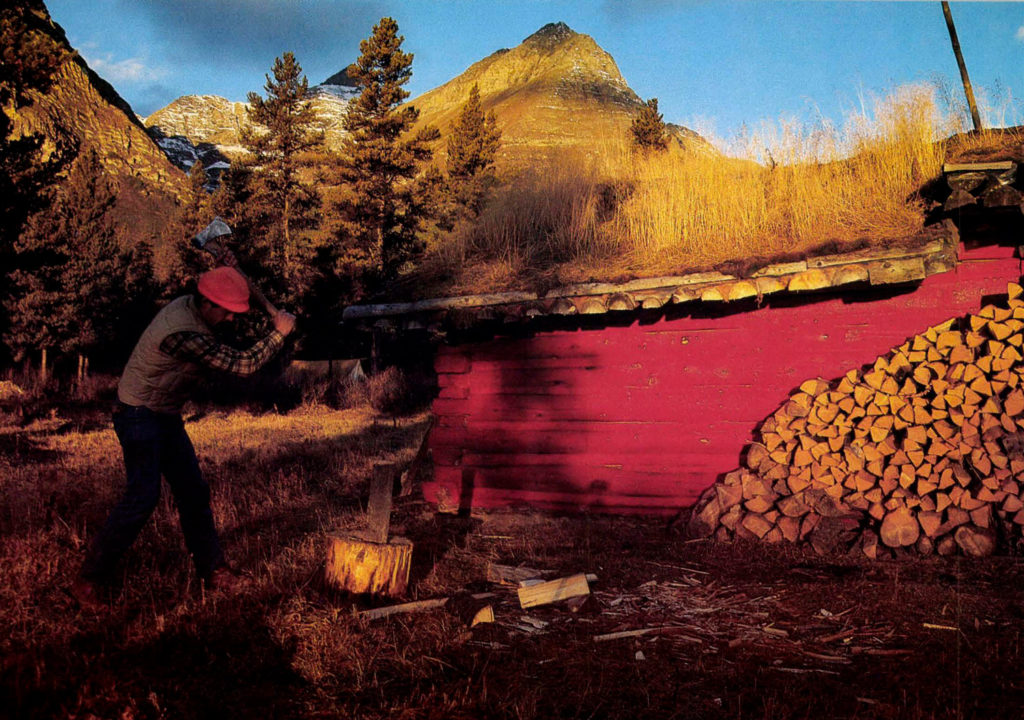

Meals were served in the barn-red log cabin with its long table, bench seats and comforting, wood- burning kitchen range. Wranglers drove the belled and hobbled horses out of the little corral beside the elevated cache every night, then herded them back each morning, clanging as they came. By the time you’d filled up on Sharron’s bacon, ham, eggs, hot cakes, toast, coffee or hot cocoa, your horse was saddled and waiting.

Don Beattie built this haven in the heart of his best moose range years ago. He’s managed this concession on the Sikanni Chief and Akie rivers since 1952, and there are valleys he still hasn’t seen. The territory stretches across 1,300 square miles from the Alaska Highway near Sikanni Chief Village west 100 miles to the Continental Divide. It’s arguably the best place to find a trophy moose. More than half of the Boone and Crockett Canada moose entries are from British Columbia, and the biggest B.C. bulls grow in this northwest corner.

I wasn’t necessarily looking for a book head, but I wasn’t planning to wave one off, either. The adventure was the main thing — coming into the country, even though it was a bit too far south for true Jack London dreams. Still, most of the central characters were here. A pine marten raced in and out of camp like an overgrown squirrel looking for meat scraps. Stone sheep grazed on the mountain flanks and above them, white mountain goats clung to the rock walls. Caribou trotted across the alpine passes, and grizzly tracks covered yesterday’s horse prints less than a mile from camp.

Don said there were wolves about, though hardly anyone ever saw them. “I saw one in Alaska once,” I said. “What I really want is to hear one. A wolf howl.” “You’d better concentrate on finding a moose, eh?” Don said. “What kind of rifle are you shooting?”

“Well, I brought two just in case a horse fell on one or something. I’ve got my old dependable, a Winchester Model 70 Featherweight in .30-06. I worked up some 200-grain Nosiers for that. Then there’s a new gun I’m trying, an Ultra Light Model 20 in .284 Winchester. I’ve got Speer 175-grain Grand Slams loaded for that. Do you think the .284 is gun enough for a moose?”

“If you can shoot straight it is.”

It’s when we set a cardboard box downrange to see just how straight I was when I discovered my problem. The pilot who had flown me in had flown my ammunition out. I’d broken my cardinal rule of storing ammunition in each rifle case. The two loose boxes had gotten kicked out of sight under a seat.

I knew the .284 was out of commission because almost no one shoots this wonderful but underrated cartridge. But the .30-06 — every camp has a few ought six cartridges lying about. John Beattie, Don’s son and my guide for the hunt, rustled through the kitchen and came up with eight rounds, 150-grain Federals. Lighter than I liked, but John said they’d do. They’d have to.

My test shot went eight inches above point of aim, and I was loath to adjust the crosshairs and use another. I’d heard too many horror stories about bulls absorbing six rounds.

“That’s close enough for a moose,” John said cheerfully. I didn’t know if he was serious or just bolstering my flagging confidence. He assured me he’d maneuver us so close I couldn’t miss, and I knew he was serious about that.

Moose have never been storied for their craftiness. You don’t go moose hunting for the challenge of outwitting the beasts, you go for the opportunity to look for them, to live in their country. That and the best meat in North America and, yes, the antlers: those massive, broad, spreading palms bristling with points. Who could want the wild North and not want those antlers?

We weren’t 200 yards from the kitchen table the first morning of the hunt when John reined his horse and looked hard at the flank of Bluebell.

“Lemme see your glasses,” he said as he reached back.

“You’ve got to be kidding. You see one already?”

I handed him the binoculars and scanned the distant slope. Lodgepole pine and balsam fir gave way to spruce which dwindles into alpine willow less than halfway up the slope. You could have seen a house cat sitting there, it seemed, but I couldn’t see anything.

“A cow and a bull,” John said without taking the binoculars from his eyes. “He looks pretty good.”

“Where?” I asked, trying not to sound too eager or too green. When I finally located the bull, it was considerably smaller than a house cat, almost swallowed by the dark patches of timber. Antlers gave him away, big, flashing white palms jutting from his head. We crossed the river, dismounted and walked within 400 yards. The rack no longer looked so impressive. The bull saw us, but he wasn’t going anywhere because a cow was lying in the bush. The rut was on.

“He doesn’t look too big to me,” I ventured, measuring him carefully against the eight racks I’d studied in camp, tokens of other men’s hunts.

“No, he’s just average. Forty-eight inches. Palms aren’t very wide. I’ve seen a better one up the valley.”

Good. I didn’t want to be forced to choose between a true trophy now and the chance for a real hunt through this stunning country. Ideally, the record- book bull should come after four or six days of hard hunting, after passing up several lesser beasts.

Our morning’s ride took us past another of those lesser moose, who was crossing a steep mountainside bordering Paradise Valley some six miles from camp. He looked a twin to the first. You could tell by the way he was moving that he was looking for cows.

That meant some old boy was holed up with the eligible gals in the area. We were looking for him.

At noon John “whoa”ed his horse in a grassy meadow and plopped down to lunch and glass. Just 19 years old, he could have ridden all day, but his old patriarch must have taught him well about accommodating greenhorns. The fewer the saddlesores, the happier the customer. Besides, John knew most moose would be bedded somewhere cool until midafternoon when lust or hunger would start them moving again.

At one o’clock thirst sent me hiking to the creek for a draught. I shouldered my rifle just in case.

Passion in moose must run as hot as it does in humans. It was midday and shirt-sleeve warm, yet a bull was cruising along the creek. I noted his direction of travel, checked the wind, and hurried downstream to intercept.

It didn’t seem possible that I could lose track of a 1,000-pound, six-foot tall beast in a skimpy line of firs, but I did. I crouched beside the noisy water and scanned the trees. Antlers unexpectedly broke from the shadows less than 40 yards away.

The bull stepped into the clear. He had seven points per side and mediocre palms. Might go 46 inches. A dynamite Shiras bull, but nothing to write home about for the Canadian subspecies. I held the Leupold crosshairs on his neck and said “bang” just for the record. Then he noticed me, turned and trotted away. I bent my face over the creek and sucked water like a wild animal.

By three o’clock we started spotting moose. The small bull I’d seen by the creek was grunting and moaning and trailing a cow and two calves. Another cow and calf moved into willows to feed farther upstream. A small bull walked within 50 yards of us.

“We’re looking for the big bull I saw in here four days ago,” John said as he swept the far mountain slope with my binoculars. “He’s the biggest I’ve seen in quite a while. He was with eight cows, so he should still be around.”

He was. John found him at 4:00, far up the valley. The white palms looked tremendous even at three miles.

“Let’s go,” I said.

“Too late.”

“What do you mean? He’s just lying there. He isn’t going anywhere.”

“I mean it’s too late to get to him and back to camp unless you want to make a long ride in the dark. He’ll be there tomorrow, eh? Want to come back for him early in the morning? Give us another ride. Might find an even bigger one, eh?”

So we hit camp at dusk with plenty of time to wash up, start a warming fire in the sleeping cabin and pull up to Sharron’s groaning table early. We’d seen two more bulls on our ride back, but neither matched the big guy far up Paradise Valley.

Next morning horse bells woke me as the last stars were dying. The smell of frying bacon lured me to the red cabin.

“Looks like another clear day,” Don said as he walked briskly to his little plane, fired up and flew off in the half-dark to check hunters and guides in his three “fly camps.”

John packed our lunches and we again aimed our horses at the snowcapped peaks bordering Paradise Valley. Frost dusted the ground vegetation, but no ice had formed at the edges of rapid Paradise Creek. I was glad to be fording it on horseback.

We stopped at the previous day’s lunch site to look for the big bull. While John was glassing, I turned to find another bull working through the willows above us.

“Look here, John. Another bull.”

“Meat bull,” he said quickly. Then he grunted something in perfect moose and the bull answered. John replied. The bull started down toward us.

Boy and beast talked back-and-forth until Bull was 50 yards out. Then John switched to English again lest the lovesick creature misunderstand our intentions.

“Go away now, moose. I was just kidding.”

Bull stood and pondered on that a while, then turned to find a less fickle companion.

I took a turn with the binoculars, checking the distant mountainside where our intended had been the previous day. He stood up from a small island of subalpine firs and shook his head.

“Okay, now let’s go.” I handed the binoculars to John, he took one look and agreed.

We were able to ride to a point directly below the moose, but then we had to tie the horses and fight up a steep slope through dense, young spruces, not the most yielding tree in the forest. A noisy creek — really a protracted waterfall — plunged down a stairstep gorge to our right.

Near the top we hit snow pock-marked with moose tracks and droppings. How a moose could get into such a dense forest amazed me, yet we could hear one groaning just ahead.

We sweated toward the sound, pushed something big from the trees, and broke into a willow “clearing” to find two cows and a small bull staring back at us. They were probably wondering how we could get through such a dense forest.

“That’s not him,” I said, as if John didn’t know.

“He’s up higher.”

We let the moose at hand saunter out of sight, then hurried up. Soon we were working around islands of stunted firs in a sea of moose-worn willows. There wasn’t a branch that hadn’t been nipped off. Tracks, droppings and old beds littered the slope. This was a real moose pasture, probably active all summer.

A strong uphill wind had developed, and I was afraid our scent would precede us to my bull. But when we rounded the edge of the last fir island, our quarry was still there, bedded with four adoring cows. “That’s him. Take him. Shoot him in the neck.”

Of course, the neck. That was the only anatomy visible above the willows. That and antlers, and I wasn’t too sure about those antlers. They didn’t look as big as I thought they should be.

“You sure this is the big one? I don’t want to shoot a smaller one then have the big one stand up.”

“This is him, this is him. He’s got the cows. Shoot him in the neck. Take your time and shoot him in the neck.”

I studied the rack again. I always hesitate and debate when the time comes to finish a hunt like this. Could I do better? Should I end it so soon? Maybe we could find an older bull up some other valley? But then I think of past hunts that stretched day after painful, gameless day. The rain-outs, the blizzards.

“Shoot, shoot before he smells us.”

I level the crosshairs on the big, black neck. The range is 125 yards. I remember the 150-grain bullets and lower the crosshairs to the tops of the willows. Before the debate can start again, I hold my breath and fire.

“Hit him again, hit him again! Give him another one.”

This strikes me funny because I have not hit him at all yet. I shot high. He merely turned to look toward us. On the next shot I have a ridiculous sight picture of willow branches where the crosshairs meet, but the bull rolls over stiffly when I pull the trigger, and the “whop” of the hit confirms it. The bull does not get up.

The cows move out grudgingly as we approach. They must have been arguing over the bull’s favors. One stays close to the fallen male, lays her ears back and rushes another cow. This belligerent one doesn’t leave until we are within 50 yards.

The dead bull is huge, of course. I am reminded of steers in Dad’s butcher shop 25 years ago. This will be work.

John is a marvel with the knife. Most American college men couldn’t be trusted to open a plastic package of cold cuts with a paring knife. John is peeling thick hide like a veteran mountain man. He butchers Indian style, laying the hide back, boning the exposed meat and never bothering to open the body cavity. It’s the same method I use. The steaks should be superb.

Within an hour we have shoulders and hams and back-straps cooling on remnant snow patches in willow shade. A half-hour more and the head is caped. We’ll be home in time for supper.

The next day we ride one last time in and out of Paradise Valley. We’ve seen at least 15 different moose, eight of them bulls, and killed the biggest.

John is talking about his rodeo rides, sitting sidesaddle, backwards, standing up on the horse. I’m singing ditties, waving to the spruce grouse and hawk owls. The pack horses are the only unhappy members of our parade, for they are carrying the winter meat supply home — that and one fine set of antlers which sport ten points per side and spread a total of 49 Inches.

“Close enough,” I said as John stretched the metal tape. “I’m going to call it 50 inches in the story. A 50- inch moose rack. I wonder where I’m going to put it?”

I lazed through the remainder of my week’s hunt, eating too many baked goodies, sleeping too long, hiking to some of the nearby trout lakes to wrestle rainbows, flyrodding a dozen big grayling from a deep river hole.

The hunt really was an affirmation of a prairie boy’s dreams. Not quite Jack London and the frozen north, but on my last night in Bluebell Camp, just three hours before Don flew me out, I awoke in the dark cabin to the unmistakable baritone howl of a wolf.